About Us

Stops & Shops

In The News

In New Mexico, on the Cowboy Trail of Jack Thorp

September 26, 2014

New York Times Travel Section

By FREDA MOON

For years, when I pictured the Rio Grande, it was as the spindly, concrete-encased trickle that marks the dividing line between the United States and Mexico. In my mind, it was as much a military installation as a body of water. But the Rio Grande can roar. It can carve an 800-foot-deep gorge into the Southwestern plateaus. It can sustain vineyards, pecan orchards, pinto bean farms and lavender fields. It can drown riverside hot springs. It can flow so fast and full that its water turns the color of adobe.

For hundreds of years, the Rio Grande Valley has been agricultural land, first farmed by the Pueblo Indians, then by the Spanish settlers who arrived in New Mexico in the 1500s. The Spaniards built haciendas, not unlike the ones that dominated the campos of “old” Mexico. They raised sheep and cattle for wool and leather and meat. With their arrival, New Mexico became cowboy country. The state would create the “cow punchers” of Western legend, nurture a cowhand nicknamed Billy the Kid and produce the famed frontiersman Kit Carson.

But that wasn’t what brought me here last February. It was a much less well-known figure: N. Howard (Jack) Thorp, “Cowboy Jack,” one of the country’s first great folk musicologists.

Thorp was born to a prominent New York family in 1867. But after boarding school (he is said to have attended Harvard briefly), he went west. He settled in New Mexico, where he worked as a rancher and surveyor. Fascinated by the music of the state’s cattle culture, he began documenting what he saw as a disappearing art form — rural poetry worthy of not only praise but preservation.

For 19 years, he traveled through New Mexico and the surrounding states, gathering ballads and poems and accumulating detailed descriptions of people and landscapes. Many of the songs seem to be as much for the cattle they were driving as they were for the cow men themselves. In “Get Along, Little Dogies,” for example, Jim Falls sings to the herd:

Whoopee ti yi yo, git along, little dogies,

It’s your misfortune, and none of my own.

In 1908, Thorp published a collection, “Songs of the Cowboys,” as a 23-song pamphlet. Two years later, much of that book was republished, uncredited, by John Lomax, who became the standard-bearer of his craft.

The perceived theft tormented Thorp, but it didn’t hold him back. He would go on to write one of the best known Western songs of his time, “Little Joe, the Wrangler” (also published, uncredited, by Lomax), he played polo with Teddy Roosevelt and provided “local color” for Conrad Richter’s frontier novels, according to Peter and Mary Ann White, who edited a 1988 edition of “Along the Rio Grande.”

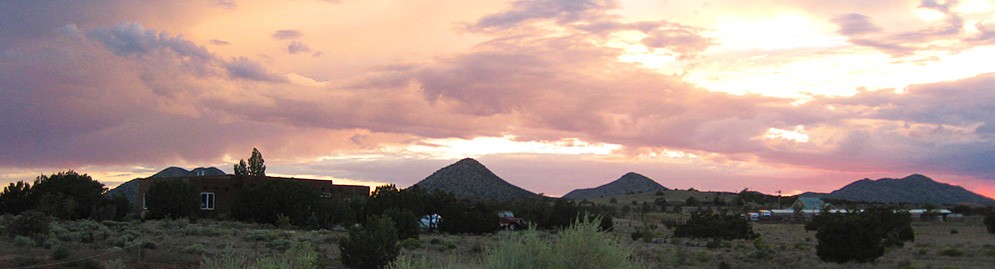

Thorp’s New Mexico is a place of overlapping cultures and harsh beauty, of cowboys and their whooping, hollering animal calls. It captures the mesquite and cat-claw thickets of tornillo bushes and encounters with the “wild and wooly” cow men of Roswell and Carlsbad.

It sounded like my kind of place.

My husband, Tim, and I flew into Albuquerque, the sprawling beige metropolis at the center of the state, rented a car and slid the disc that accompanied a beautifully illustrated centennial rerelease of Thorp’s “Songs of Cowboys” into the CD player. On the CD, the Western historian and musician Mark L. Gardner and Rex Rideout perform 17 songs from Thorp’s collection. In “The Texas Cowboy” the lyrics go

Yes I’ve traveled lots of country,

Arizona’s hills of sand

Down through the Indian Nation

Plum to the Rio Grande

Montana is the bad-land

The worse I’ve ever seen

Where the cow-boys are all tenderfeet

And the doggies are all lean.

It was a fitting soundtrack to a five-day, nearly 900-mile road trip through the Land of Enchantment, a state that lives up to its moniker.

The trip’s natural starting place was in the north, with Taos and one of New Mexico’s newest national parks, the Rio Grande del Norte National Monument, about 150 miles from Albuquerque, which makes up 240,000 acres of Taos County. After checking in at the Taos Inn, where there was a kiva fireplace in our room and a legendary margarita list in the lobby’s Adobe Bar, Tim and I drove north. Eventually, we turned onto a dirt road through a narrow canyon cut with a rushing stream that made me wish for a pickup truck in place of our Prius.

The creek we’d been following dead-ended at a wide river and a narrow bridge, where we parked and walked to the trailhead for Black Rock Hot Springs. The path was marked with a rock painted with yellow letters: “This land is sacred.” At first it seemed we had the spot to ourselves. But then, behind a boulder, I spotted a baseball cap, sunglasses, an unclothed body — an older man so serene, I wasn’t sure he’d registered our arrival. “Can we join you,” I asked. “That’s what it’s for,” he said. The smooth rocks were covered in green algae and fine, sparkling sand. The three of us sat in the pool in a silence that wasn’t nearly as awkward as it could have been. Looking around me, I imagined Thorp, a former New Yorker, riding the canyons of the Southwest by horseback.

Through rocky arroyos so dark and so deep

Down the sides of the mountains so slippery and steep

You’ve good judgment, sure footed, wherever you go

You’re a safety conveyance my little Chopo.

He wrote “Chopo” about a horse in Sierra Blanca, Tex., but the line could just as easily have been about the harsh beauty of the northern Rio Grande.

These days Taos and the state capital, Santa Fe, are better known as the home of artists, New Agers and spagoers than cowboys and their songs. But signs of the state’s history are everywhere. After our soak, Tim and I stopped at Taos Mesa Brewing, a craft brewery in a Quonset hut outside town, which hosts both modern art and a weekly two-step dance series with music by bands like the Far West and Lonesome Town. On Taos’s main drag, Paul’s Western Wear coexists with pottery shops and galleries. On the outskirts of town, Hacienda de los Martinez is a 21-room adobe (circa 1804) that was once the northern terminus of the Camino Real and is now a museum that recreates life on the estancia.

En route to Rancho Gallina, an old ranch house turned Airbnb rental, where I’d reserved a room for later that night, we stopped in Santa Fe, Thorp’s home during his years with the Federal Writers’ Project. I was thrilled to catch the New Mexico History Museum at the very tail end of its “Cowboys Real and Imagined” exhibition, which incorporated both Thorp’s work and his themes. Afterward, I drank a Shiner Bock and ate a green chile hamburger at Cowgirl BBQ, where the tables were draped in picnic print oilcloth and the décor was mounted horns and western movie posters.

At Rancho Gallina, we were greeted by a couple, Mitch Ackerman and Leslie Moody, who had been labor organizers in Washington, D.C., before they bought the 10-acre ranch. They were renovating the property, which was built in the 1930s for a couple who bred Arabian horses, and the former stables were being converted to a kitchen-dining room. Showing us around, Mr. Ackerman pointed to branding marks on the ceiling above the patio fireplace. “Cowboy graffiti,” he said.

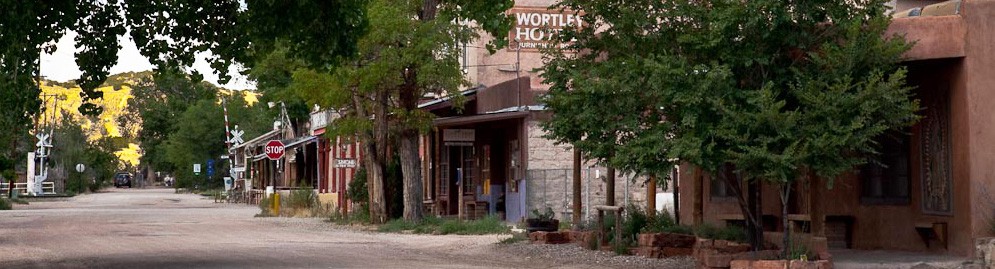

After a cocktail at the Rancho, Tim and I drove into Madrid (pronounced MAD-rid), a former mining company town that was thriving during Thorp’s day. It was later offered for sale, in its entirety, in the 1950s. The asking price was $250,000. There were no takers.

It’s a quirky little place: art colony meets penal colony. We ate dinner at the Mineshaft Tavern, where the server was a middle-aged woman with a silver buzz cut, a turtle tattoo on her shoulder and a tank top that read, “Welcome to Madrid — Madrid has no town drunk. We all take turns.”

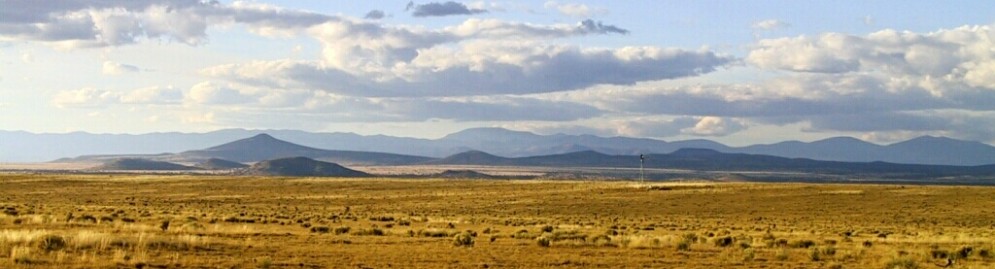

From Madrid, we drove and drove, heading south along straight, flat state roads and through Estancia, where the newspaper that published Thorp’s pamphlet once occupied a stately corner in what is now a sad, desperate downtown. We passed through miles of eastern New Mexican ranchland, parched fields and ancient windmills.

At Carrizozo, home of the Bar W Ranch, where a young Thorp worked as a cowboy for a few years, we cut east to Lincoln. This was where Billy the Kid spent his final, fateful days and where we slept in a creaky, doily-adorned B & B that had a “Billy the Kid Slept Here” sign out front and flawless eggs Benedict the next morning. Then we drove south to the impressive New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum in Las Cruces, where the Rio Grande was nothing but a gravel gully. We spent a night at a 1950s-era motel, La Paloma, in Truth or Consequences, formerly Hot Springs, N.M., which Thorp described as being in the midst of a “speculative boom” in the 1920s.

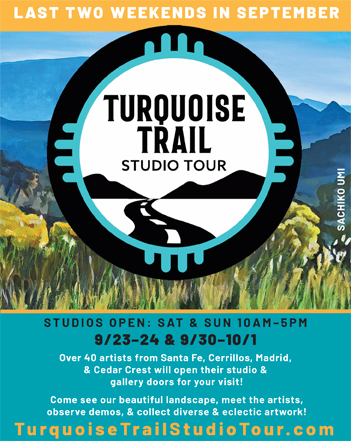

But because no trip along Thorp’s trail would be complete without some time on horseback, I booked a ride with Broken Saddle Riding Company. We arrived at Cerrillos Hills Historic Park before 9 a.m. During its height, in the late 1800s, Cerrillos had thousands of residents, several churches and hotels and more than 20 saloons. Today, one could be forgiven for thinking that dogs and trail horses outnumber humans. My horse, a regal Tennessee walking horse named Abby, reminded me of Thorp and his “Ti Ri Youdy,” a previously unpublished piece from Mr. Gardner’s book that opens with “Well boy you see I’m back, on my old red roan ... ”

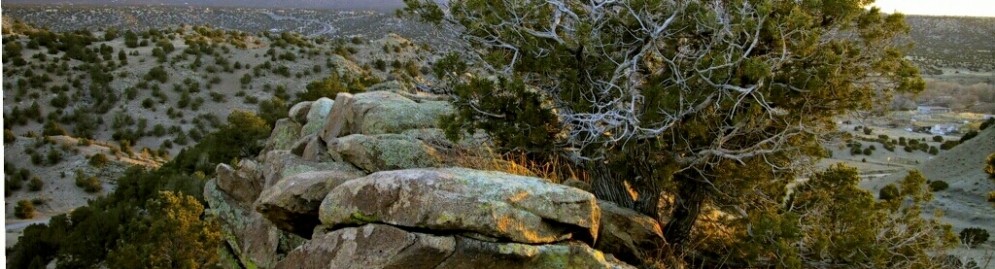

These hills were once home to some of the most prolific turquoise mines in the country, explained Carl, our guide. Originally from Oregon, he looked every bit the grizzled cowboy, with leather chaps, a handlebar mustache and a bandanna around his neck. As we rode, I scanned the ground for renegade gemstones. But it was Carl who spotted one first. Swinging from his horse, he plucked the soft blue rock from underfoot. “That right there is up to Charles Tiffany’s standards,” he said. He placed the stone in my gloved palm, an unpolished souvenir. It was the color of the sky. As we passed juniper, pinyon pine and prickly pear, Carl rattled off the culinary and medicinal properties of each. Then there was cholla. “The only reason I can think that it was put on earth,” he said of the snaking cactus, “was to bring heartache and sorrow to mankind.”

But as one verse in “Get Along, Little Dogies” makes clear, cholla was worth more than heartache during Thorp’s day:

Your mother was raised way down in Texas,

Where the jimson weed and sand-burrs grow;

Now we’ll fill you up on prickly pear and cholla,

Till you are ready for the trail to Idaho.

IF YOU GO

Rancho Gallina Inn and Eco Retreat, 31 Bonanza Creek Road, Santa Fe; ranchogallina.com.

Los Poblanos Historic Inn & Organic Farm, 4803 Rio Grande Boulevard, N.W., Los Ranchos de Albuquerque; lospoblanos.com.

Ellis Store Country Inn, Highway 380, mile marker 98, Lincoln; ellisstore.com.

La Paloma Hot Springs and Spa, 311 Marr Street, Truth or Consequences; lapalomahotspringsandspa.com.

Construction Alert

Details about roadway construction on NM 14Upcoming Event

Cerrillos Fiesta

TBAAnnual Cerrillos Fiesta - date TBA

Event details » View all events »